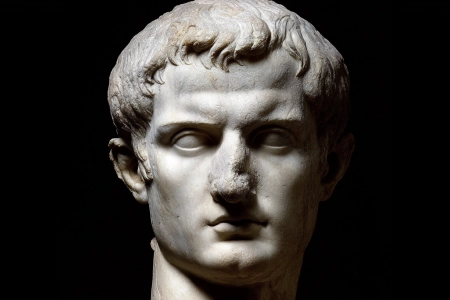

Caligula: A Biography of Rome's Most Notorious Ruler

Explore Caligula's rise, rule, and assassination.

Introduction

Born Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus at Antium in 12 CE, the third Roman emperor is remembered by his childhood nickname Caligula (“little boots”), earned while accompanying his father Germanicus among the Rhine legions. His short reign, 37–41 CE, became a byword for the “mad emperor.” This biography looks past legend to ask who Caligula was, what he did as ruler, and why a palace conspiracy ended his life on 24 January 41 CE. Along the way, we treat the ancient evidence as evidence — not gossip — weighing senatorial hostility in writers like Suetonius and Cassius Dio against the more situational viewpoint preserved by Philo of Alexandria during the Alexandrian embassy crisis.

Family, Childhood, and the Making of “Caligula”

Germanicus, adopted by Tiberius and beloved by the army, and Agrippina the Elder, Augustus's granddaughter, gave Gaius impeccable pedigree within the Julio-Claudian dynasty. As a charming child in miniature gear, he toured frontier camps and earned the nickname Caligula from soldiers' caligae (hobnailed boots). After Germanicus's death (19 CE) and Agrippina's exile, the family suffered purges, teaching the young prince the arts of silence and survival at court. Brought later to Capri, he observed Tiberius's suspicious court politics at close range.

Accession and the Golden Months (37 CE)

When Tiberius died in 37 CE, his will named Gaius co-heir with Tiberius Gemellus. With decisive help from the Praetorian Prefect Macro, the Senate acclaimed Caligula as emperor. Early measures won acclaim: remitting unpopular taxes, granting bonuses to the Praetorians and urban populace, recalling exiles, and staging lavish games. Rome embraced the youthful princeps after years of Tiberian secrecy. That same year, however, a serious illness struck. Ancient authors frame a post-illness “change,” but modern historians note that as Caligula asserted power, senatorial hostility sharpened.

Caligula and the Senate: Performance, Power, and Payback

Caligula pressed an increasingly monarchical style. He demanded deference, revived or manipulated maiestas (treason) trials, and performed authority through spectacle and public humiliations. Senators recorded this as tyranny; for the emperor, it advertised who ruled. Meanwhile the Praetorian Guard—kingmakers then and later—enjoyed favor, pay, and proximity. The triangle of emperor, Senate, and Guard generated the tensions that fill ancient narratives.

Policies at Home: Taxes, Games, and Administration

Taxes & Finance

Early tax remissions and lavish spectacles pleased crowds but strained revenue. Later stories of financial crisis blend reality (high spending, extraordinary levies, auctions, and confiscations) with hostile exaggeration. Caligula also pressed provincial extractions—typical of emperors balancing army and urban costs.

Games & Public Works

The regime invested in gladiatorial shows and chariot races, reinforcing the image of the princeps as provider — and reminding Romans that entertainment was also propaganda. If you want the bigger story of Rome’s spectacle economy, see The Roman Colosseum: Arena of Blood, Glory, and Empire. Construction and embellishment on the Palatine Hill (and headline-grabbing stunts at Baiae) fed both popularity and later legend.

Administration & Elites

Caligula raised capable equestrians to key roles and managed client kings. To senators, the promotion of non-senatorial elites read as insult; to an emperor, it was practical governance and faction-balancing.

A Luxury Signal: The Nemi Ships

One of the most vivid archaeological echoes of Caligula’s taste for display is the pair of enormous vessels built on Lake Nemi — often described as floating palaces, fitted with marble decoration and complex plumbing/fixtures. They were recovered in the early 20th century and displayed in a dedicated museum, but were destroyed by fire in 1944; the modern museum preserves the story (and surviving fragments) as a reminder that Caligula’s reputation was shaped not only by texts, but by real imperial engineering projects.

Religion and the Imperial Cult

Caligula emphasized the sacral aura of emperorship, experimenting with divine iconography and accepting ruler cult honors where Greek practice allowed. In Judea, reports by Philo of Alexandria speak of a crisis over placing the emperor's statue in the Jerusalem Temple—averted before completion. Whether read as megalomania or policy, the message was clear: loyalty to Rome had a religious dimension.

Abroad: Britain, Germany, and the “Seashells”

Caligula assembled forces near the Channel and staged coastal maneuvers that ancient authors mocked. The famous anecdote of collecting seashells as “spoils of the ocean” reads like farce in hostile retellings, but can also be read as morale theater and symbolic messaging when a Britain operation stalled. (For Rome’s later crisis in Britain, see Boudica: The Celtic Queen Who Led a Rebellion Against Rome.)

Court, Family, and Scandal

Caligula's marriages and relationships—especially the closeness to his sisters, notably Drusilla—fueled scandalous storytelling in Suetonius. Behind gossip lay politics: imperial households brokered alliances; sudden shifts in favor created enemies; and the emperor's public intimacy—banquets, entrances, staged appearances—was itself a language of rule.

The Assassination: Who Killed Caligula—and Why?

On 24 January 41 CE, a palace conspiracy led by Cassius Chaerea of the Praetorian Guard attacked Caligula after a performance, killing him and, amid chaos, his wife Caesonia and their infant daughter. Motives mixed personal grievance, fear provoked by humiliations and trials, and senatorial resentment. While the Senate mused about restoring the Republic, rank-and-file Praetorians found Claudius in the palace and proclaimed him emperor, confirming the Guard's role in succession.

Myth vs. History: Sorting the Stories

Was Caligula “Insane”?

Ancient authors deploy madness to moralize about absolute power and to justify assassination. Modern readings see performance politics pushed beyond senatorial taste, plus genuine erratic episodes—not proof of total derangement.

Did Caligula Make His Horse Consul?

No reliable evidence that Incitatus held office. The tale likely satirizes Caligula's contempt for the Senate, implying he could elevate anyone—even a horse—above them.

The “Seashells” Campaign

Suetonius and Cassius Dio describe soldiers collecting shells as “spoils of the ocean.” Read as ritualized theater and propaganda during a postponed crossing, not literal conquest.

The Bridge at Baiae

A pontoon bridge over the Bay of Baiae, ceremonially crossed by the emperor, signaled wealth and control. Technically feasible, it showcased imperial command more than delusion.

How Reliable Are the Sources?

We rely on Suetonius, Cassius Dio, and Philo of Alexandria, each writing with agendas, at distance, or from elite perspectives. Critical reading and corroboration are essential.

The Ancient Evidence: Who Tells Us About Caligula?

Caligula’s image survives through a filter: most narratives were written by elites who either disliked his style of rule, or had reasons to explain (and justify) his violent removal. Reading Caligula responsibly means asking who is speaking, when, and why.

| Source | Perspective | What it’s best for | What to watch for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suetonius | Imperial biographer; moralizing portraits | Vignettes of court life, rumor, character sketches | Scandal-first storytelling; anecdotes can be sharpened for effect |

| Cassius Dio | Senatorial historian writing later | Political framing of emperor vs. elite | Retrospective “tyrant” template; speeches are often literary |

| Philo of Alexandria | Contemporary outsider (Alexandrian Jewish leader) | Embassy crisis, imperial reception, religious tension | Rhetorical aims; still invaluable for an on-the-spot viewpoint |

| Josephus | Later narrative with political detail | Assassination sequence and immediate aftermath | Uses sources selectively; shaped by his own agendas |

| Seneca | Philosopher close to power (later) | Illustrations of cruelty, fear, and court danger | Examples can be stylized to teach moral lessons |

Caligula's Rome: Daily Life Under the Princeps

For the urban plebs, the reign meant frequent spectacles and a visible emperor. For senators, it meant anxiety about status and safety. For the Praetorians, it meant pay and proximity to power—until the blades turned inward. In the provinces, governors balanced taxation, justice, and the emperor's sacral messaging.

Modern Reassessments: Why Caligula Still Trends

Caligula remains a click-magnet because he sits at the intersection of scandal, power, and unreliable sources — and because new scholarship and media keep refreshing the conversation. Used carefully, modern headlines can add nuance rather than sensationalism:

- Scholarship (2025): Recent research has revisited Caligula’s image through unexpected lenses — a reminder that hostile sources can still preserve real details.

- Pop culture (2024): New edits/releases of Caligula have renewed public interest and search traffic around the emperor’s reputation.

Caligula and the Julio-Claudian System

The Julio-Claudian Principate rested on adoption, dynastic prestige, and army loyalty rather than hard law. The Senate kept honor without decisive power; the Praetorian Guard gained leverage as maker and unmaker of emperors. Caligula pressed a more sacral monarchy than Augustus had veiled. The elite recoil—and his death—reveal the system's limits.

Timeline: Life, Reign, and Legacy

- — Birth of Gaius (Caligula) at Antium.

- — Death of Germanicus; family conflict with Tiberius.

- — Gaius to Capri; learns court politics.

- — Caligula becomes emperor; early popularity; serious illness.

- — Tense Senate relations; spectacles; religious controversies.

- — Northern displays; Baiae bridge; “seashells” anecdote.

- — Assassination by Cassius Chaerea; Claudius succeeds.

Conclusion: Caligula's Place in Roman History

Strip away sensationalism and Caligula remains a revealing figure of the Julio-Claudian order: a princeps who turned theater into policy, punished elites, and sacralized his rule. His fall—engineered by Praetorians and tolerated by senators—underscores Rome's governing logic: keep the soldiers, feed the crowds, and manage the aristocracy. Fail, and even an emperor can die in a corridor.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why was Caligula assassinated?

Ancient narratives point to a mix of Praetorian grievances, fear fueled by humiliations and treason accusations, and senatorial hostility. The conspiracy crystallized around officers such as Cassius Chaerea, and it succeeded because the Guard controlled access and momentum inside the palace.

What did Caligula really do as emperor?

He began with crowd-pleasing gestures (tax relief, games, recalls of exiles), then asserted authority in ways elites found intolerable — blending spectacle, punishments, and a more openly monarchical style. The gap between popularity with some urban audiences and hatred among many senators is central to his story.

Was Incitatus made consul?

No reliable evidence shows Incitatus held office. The story functions best as political satire — a way to say Caligula could elevate anyone above the Senate.

Did Caligula really declare himself a god?

He leaned hard into the language of divine honors and ruler-cult messaging (especially where Greek practice made that easier). Whether this was “madness” or calculated politics, it signaled that loyalty to Rome could carry a religious charge.

What were the Nemi ships used for?

Their exact purpose is debated, but they likely served as ceremonial luxury platforms — an extreme display of wealth, engineering, and imperial leisure on Lake Nemi.

Did Caligula plan to invade Britain?

He clearly mobilized and staged operations near the Channel, but the invasion did not happen under his reign. Ancient writers mock the episode; modern interpretations often treat it as a mix of reconnaissance, logistics, and political theater.

How reliable are the sources on Caligula?

We depend heavily on Suetonius and Cassius Dio (both shaped by elite memory), while Philo provides a valuable outsider view during a real political crisis. Reading across sources — and separating anecdote from corroborated pattern — is essential.

What happened after Caligula’s death?

The Senate hesitated and some dreamed of restoring the Republic, but the Praetorians moved faster, proclaiming Claudius and making the military basis of the Principate unmistakable.

Sources & References

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars (Caligula).

- Cassius Dio, Roman History (Books 59–60).

- Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius (Legatio ad Gaium).

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews (Book 19, on the assassination and aftermath).

- Seneca, On Anger (court cruelty anecdotes and moral framing).

- Anthony A. Barrett, Caligula: The Corruption of Power (Yale University Press).

- Aloys Winterling, Caligula: A Biography (University of California Press).

- Mary Beard, SPQR (context for the early Principate).

- Museum of the Roman Ships (Nemi) — background on the Nemi ships and the 1944 destruction.

More Articles