The Printing Press and the Birth of the Modern World

Printing Press History

Introduction

Few inventions reshaped human society as completely as the printing press. In the mid-1400s, a metalsmith from Mainz named Johannes Gutenberg combined movable type, oil-based ink, and a screw press to create a reliable, repeatable way to copy text. This article offers a concise, evidence-based guide to printing press history—from its technical breakthrough to its vast cultural effects. In the century that followed, print fueled the Renaissance, supercharged the Reformation, and laid foundations for the Scientific Revolution by making ideas cheaper to produce and quicker to spread.

From Movable Type to Momentum: The Gutenberg Printing Press in Context

Gutenberg worked in the Rhineland, where metallurgy and wine-press technology were well known. His crucial insight was to cast thousands of tiny metal letters—type—of consistent height, which could be arranged, inked, and pressed onto paper, then redistributed for the next page. The system united three elements: durable metal type, a press adapted from existing screw presses, and an ink that adhered cleanly to metal and transferred to paper. A hand compositor could set lines rapidly; a pressman could pull hundreds of impressions a day.

What made the Gutenberg printing press distinctive was the way it combined existing techniques into a powerful system:

- Metal movable type cast from a durable lead—tin—antimony alloy, so individual letters could be reused thousands of times.

- A screw press adapted from wine and oil presses, applying even pressure across the whole page.

- Oil-based ink that stuck well to metal type and produced sharp, repeatable impressions on paper.

Movable Type Before Gutenberg

- In East Asia, printers perfected woodblock and movable-type systems long before Gutenberg, but character-rich scripts, costly materials, and different book markets limited large-scale adoption.

- In Europe, a relatively small alphabet, growing paper production, and dense merchant networks made movable type ideal for rapid, commercial book production.

Movable type was not a purely European invention. As early as the 11th century, Bi Sheng experimented with ceramic type in China, and Korean printers produced the metal-type Jikji in 1377. Different writing systems, materials, and market conditions shaped very different trajectories. Gutenberg's system proved uniquely scalable within Europe's Latin alphabet, paper networks, and urban merchant culture—turning a craft breakthrough into mass industry.

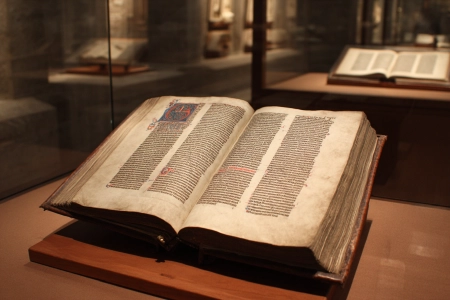

The Gutenberg Bible and the World of Incunabula

Scholars generally estimate that roughly 180 copies of the Gutenberg Bible were produced on paper and vellum. Fewer than 50 are known to survive today, many incomplete, held by major libraries and museums. The point was not just beauty—it was repeatability: a text could now be reproduced with a consistency that manuscript culture rarely matched, and at a scale that quickly changed Europe’s information economy.

Around 1454-55, the Gutenberg Bible (42-line Bible) demonstrated unprecedented clarity and uniformity. It looked like a fine manuscript but could be produced in dozens of copies—astonishing for the time. Books printed before 1501 are known as incunabula (“in the cradle”), a term marking the technology's formative decades. By 1500, presses operated in more than 200 European towns, from Venice and Basel to Paris and Nuremberg, with millions of sheets in circulation.

Incunabula by the Numbers

- What counts as incunabula? Books printed in Europe up to 1500 (with 1501 as the practical cutoff)—a convenient but ultimately arbitrary boundary later adopted by cataloguers.

- How many exist? Major catalogues list 30,000+ distinct 15th-century printed editions, with surviving copies dispersed across thousands of collections.

- Why this matters: Even before the 1500s ended, print had already become a continent-wide system for knowledge dissemination, standard reference, and commercial publishing.

Inside the Workshop

-

Typefounding

Punch → matrix → cast individual sorts at uniform “type height.”

Key tools: Punches, matrices, hand mould, lead-tin-antimony alloy

-

Composition

Arrange sorts into lines, assemble pages, and lock the forme.

Key tools: Composing stick, galleys, quoins, chase

-

Inking & Impression

Apply oil-based ink and pull the sheet on a screw press.

Key tools: Ink balls/rollers, tympan & frisket, screw press

-

Finishing

Dry sheets, add rubrication by hand, and bind the book.

Key tools: Drying racks, pens/brushes, bindery press

-

Proofing & Corrections

Pull trial sheets and check them aloud or line by line for broken type, inverted letters, and spelling errors before committing to a full print run.

Key tools: Corrected formes, scrap sheets for proofs, hand-written errata notes.

-

Storage & Distribution

Bundle and store finished sheets or bound volumes, then move them into the networks of book fairs, travelling peddlers, and urban bookshops.

Key tools: Wooden chests, packing materials, account books, trade fairs, and local booksellers.

Impact of the Printing Press on the Renaissance and Reformation

The press magnified the Renaissance by enabling quick reproduction of classical texts, grammar books, and humanist commentaries. Printers such as Aldus Manutius in Venice popularized handy formats and scholarly editions, spreading Greek and Latin works far beyond elite scriptoria. Typography itself became a competitive advantage: distinctive typefaces and careful editing built trust and brand recognition.

Many of the people who define the 15th century in popular memory were also shaped by this new print culture. Biographies of figures such as Joan of Arc, conquerors like Mehmed II, and explorers in the age of Christopher Columbus reached wider audiences because printers turned manuscript stories into repeatable books and pamphlets. Later, artists and engineers such as Leonardo da Vinci worked in a world where printed diagrams, treatises, and classical texts circulated more quickly than ever before.

Pamphlets, Polemics, and the Printing Press Reformation

After 1517, print became the engine of religious controversy. Broadsheets and pamphlets translated complex theology into vivid arguments and images. Luther's works circulated by the hundreds of thousands within a decade, while opponents used the same tools. Printers responded to demand: short, cheap formats sold fast, inviting rapid reply. Print did not cause the Reformation, but it supplied the channels—and the speed—that made it a continent-wide public debate.

Scale mattered. One widely cited scholarly estimate suggests that millions of copies of Luther’s writings circulated in print within the first decades of the movement—evidence that controversy, once printed, could travel faster than institutions could respond. This was the new logic of public persuasion: short works, rapid reprints, and near-immediate counterarguments—a feedback loop powered by presses and buyers.

Historians sometimes speak of a “pamphlet storm” in these years. In German lands alone, tens of thousands of short Reformation tracts appeared between the 1510s and 1540s, with Luther's works reaching print runs in the hundreds of thousands. Printers favored titles that sold—religious controversy, political news, and gripping polemic—so the impact of the printing press depended not just on technology, but on the commercial instincts of printers and the curiosity of readers.

Fast Facts

-

Pamphlets

Short formats (≈8-16 pages) were cheap, fast to print, and easy to distribute.

Why it mattered: Accelerated public debate and reply cycles.

-

Images

Woodcuts and later engravings carried arguments visually for semi-literate audiences.

Why it mattered: Expanded readership and persuasion.

-

Controls

Licensing, censorship, and indexes tried to police print.

Why it mattered: Printers adapted (cross-border printing, pseudonyms).

-

Vernacular Languages

Translations into local languages (German, French, English) rapidly expanded readership.

Why it mattered: Put scripture and polemics in readers' hands, fueling debate and reform.

Printing Press and the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution relied on reproducible texts, diagrams, and data. Standardized print made it easier to compare observations, correct errors, and build on prior results. In 1665, two early scientific periodicals signaled a new era of regular, public knowledge exchange: France’s Journal des sçavans (first issued in January 1665) and the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions (first published in March 1665). Tables, fold-out illustrations, and errata became routine tools for scrutiny and replication. Print also stabilized terminology, enabling scholars in different cities—and languages—to speak more precisely about shared problems.

Print fixed texts, stabilized terminology, and amplified intellectual output—key preconditions for cumulative science.

From Andreas Vesalius's illustrated anatomy books to the astronomical works of Copernicus and, later, Galileo, many landmark texts of the printing press scientific revolution relied on reproducible diagrams as much as on words. Once a diagram could be printed accurately in dozens or hundreds of copies, other scholars could check measurements, repeat experiments, or challenge claims, creating a feedback loop between workshops, observatories, and learned societies.

Ripple Effects: Rise of Literacy and Knowledge Dissemination

As book prices fell and supply rose, more people encountered print—in school primers, almanacs, chapbooks, catechisms, and ballads. The rise of literacy was uneven and slow, but over centuries it shifted expectations about learning and authority. Print helped standardize spelling and grammar, which aided administration and education. It supported new reference genres—dictionaries, atlases, and encyclopedias—that organized knowledge for reuse. For merchants and states alike, reliable printed numbers and laws were powerful.

The public sphere—coffeehouses, bookshops, salons—grew around this steady flow of affordable information. While conversation and handwritten notes still mattered, the printed page set the pace.

Print also carried darker material: broadsides about executions, lurid crime stories, and narratives of persecution and plague. The same medium that spread humanist scholarship helped fix in memory episodes like the Black Death, sensationalized witch trials, and inquisitorial prosecutions later explored in our articles on the Dark History of the Inquisition and Elizabeth Báthory. Early modern readers were already living with a kind of information overload, choosing between edifying and sensational print much as we do online today.

Debates and Myths: The “Invention of the Printing Press”

The phrase “invention of the printing press” can mislead. No single person discovered print from nothing; rather, artisans across regions assembled solutions to common problems. Gutenberg's particular combination—metal movable type, a durable press, and oil-based inks—proved commercially transformative in Europe. The wider story includes East Asian innovations in woodblock and metal type, as well as later mechanical improvements (e.g., the 19th-century steam press) that multiplied speed again.

Another myth is that print instantly made everyone literate. In reality, change unfolded over generations. Print accelerated learning where schools, languages, and markets supported it; elsewhere, impact was gradual.

Print, Economy, and Politics

Printing was a business. Risk-taking printers needed capital, fonts, paper contracts, and distribution partners. Successful houses built brands through type design and editorial standards. Politically, pamphlets and newspapers helped shape “imagined communities,” aligning readers who never met but shared news and language. Governments recognized the power of print—supporting official gazettes, taxing paper, and attempting control—yet complete control proved elusive in a market hungry for information.

Print also standardized practical knowledge—from legal codes to technical handbooks and military manuals—which complemented transformations like the Gunpowder Military Revolution.

The earliest print shops were also start-ups—capital-intensive and risky. Gutenberg’s own venture depended on financing and tight coordination between craft roles (typefounders, compositors, pressmen, binders). When disputes over debt and ownership erupted, court actions helped shift control of the Mainz operation away from Gutenberg. It’s a reminder that the impact of the printing press was never just technical—it was shaped by credit, contracts, and competition.

- Censorship and licensing: States and churches experimented with licenses, pre-publication review, and banned-book indexes to control what could be printed.

- Underground presses: When controls tightened, controversial works moved to cross-border or clandestine presses, with books shipped in barrels, bales of cloth, or false-bottomed crates.

- Authors' rights: Disputes over who could profit from a successful book eventually helped inspire early copyright laws, a reminder that the economics of print have always shaped what gets published.

Conclusion: The Press's Long Shadow

The printing press did not create ideas, but it multiplied their reach and pressured institutions to respond. By standardizing texts, accelerating debate, and widening access, it remade culture, religion, science, and politics. Our digital networks extend this story: the challenges of credibility, speed, ownership, and control all echo early modern print culture. To understand today's information world, it helps to know how the first revolution in mass communication began.

If you'd like to explore more of the world that grew up around the press, see other 15th-century stories on History Prime—from Joan of Arc and Mehmed II to Machu Picchu, Columbus's 1492 voyage, and Leonardo da Vinci. Together they show how war, exploration, faith, and invention intertwined in the same transformative century that produced the printing press.

Later communication breakthroughs follow the same pattern—see how the next wave unfolded in The Telephone: Invention and Global Impact.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Printing Press

Was Gutenberg really the first to invent the printing press?

No. Block printing and movable type existed in East Asia centuries earlier. Gutenberg's achievement was to combine metal movable type, a powerful screw press, and oil-based inks into a system that could be scaled and commercialized in 15th-century Europe.

How many Gutenberg Bibles survive today?

Historians think around 180 copies were originally printed on paper and vellum. Today, fewer than fifty survive, many incomplete, held in major libraries and museums around the world.

Did the printing press immediately make everyone literate?

No. Literacy rose slowly and unevenly over several centuries. The printing press made books cheaper and more abundant, but schooling, language policy, and economic conditions determined who could actually learn to read.

How is the printing press similar to the internet?

Both technologies drastically lowered the cost of copying and sharing information, created new opportunities for learning and collaboration, and raised fresh concerns about misinformation, censorship, and information overload.

Why does “incunabula” end at 1500 (or 1501)?

The cutoff is mainly a cataloguing convention—useful for historians, but not tied to a single technical breakthrough. It marks the “cradle” period of European print before production exploded in the 1500s.

What made Gutenberg’s system succeed in Europe?

Europe’s alphabetic writing system, expanding paper supply, dense trade networks, and rising urban literacy created ideal conditions for scalable movable type. Gutenberg’s achievement was a complete, repeatable production system—type, ink, press, and workflow—that could be copied and improved by competitors.

Sources & References

- Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (Cambridge University Press, 1979).

- Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed., 2005).

- Lucien Febvre & Henri-Jean Martin, The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450–1800 (Verso, rev. ed., 2010).

- Andrew Pettegree, The Book in the Renaissance (Yale University Press, 2010).

- Adrian Johns, The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making (University of Chicago Press, 1998).

- Library of Congress, Gutenberg Bible collection resources and essays (print run estimates, survival counts, and historical context).

- The Royal Society, background materials on Philosophical Transactions and its 1665 launch under Henry Oldenburg.

- Incunabula Short Title Catalogue (ISTC), hosted by CERL — bibliographic database for 15th-century European printing.

- British Library, collection overviews on the Gutenberg Bible and incunabula (early European printed books).

- Documentaries/Lectures: BBC The Machine That Made Us; university lecture series on early modern print culture and the history of the book.

More Articles