Leonardo da Vinci: Renaissance Genius

Inside Leonardo’s world of workshops, courts, and notebooks—where curiosity became innovation.

Introduction

Few names from the Renaissance are as instantly recognizable as Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci. Painter and draftsman, engineer, anatomist, and tireless observer, he became the clearest example of a Renaissance genius — not because he mastered one craft, but because he treated art as a way to investigate reality. Living from 1452 to 1519 CE, Leonardo moved through the power centers of his age — Florence, Milan, Rome, and finally France — as courts competed for talent, prestige, and practical expertise.

This article offers a clear, accessible Leonardo da Vinci biography that explores him as both artist and scientist. It examines his artworks, inventions, drawings, and notebooks, from paintings such as Mona Lisa and La Belle Ferronnière to iconic studies like The Vitruvian Man, and explains how Leonardo da Vinci changed the world—and why he is still considered the model of the universal human intellect, the ultimate polymath.

Why Leonardo Still Matters

- Art innovation: He pushed realism through light, anatomy, and composition — influencing European painting for centuries.

- Notebooks: His sketches and notes preserve a working mind in motion — experiments on bodies, water, machines, and optics.

- Engineering vision: Many designs were conceptual, but they expanded what patrons and builders thought was possible.

- The “Renaissance man” ideal: Leonardo became the symbol of curiosity across disciplines, not just talent in one.

Origins of a Renaissance Genius (1452–1482 CE)

Leonardo was born on 15 April 1452 CE in Vinci, a small town in the Republic of Florence. The illegitimate son of a notary, Ser Piero, and a peasant woman, Caterina, he grew up between town and countryside. This mattered more than it might seem. Surrounded by hills, streams, plants, and animals, young Leonardo developed a habit of careful observation that would shape his entire life.

In his teens he entered the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence, one of the most important centers of artistic training in Italy. Here he learned the skills of a painter and sculptor, but also engineering basics: casting metal, designing stage machinery, and solving practical problems. Some early Leonardo da Vinci artworks, like his contribution to Verrocchio’s Baptism of Christ, already show his fascination with light, motion, and natural detail.

Florence in the later 15th century was a hub of Renaissance thought, thriving under the influence of the Medici family. Humanist scholars revived classical texts, while artists experimented with perspective and anatomy. This is the same world explored in the 15th Century overview and in topics like The Printing Press and the Birth of the Modern World , which explains another key innovation of Leonardo’s age. Together, these changes created the environment that allowed a figure like Leonardo to flourish.

Leonardo da Vinci as Artist and Scientist

Masterpieces of a Renaissance Genius

Leonardo’s reputation as a Renaissance genius rests first on his paintings. While he completed relatively few works, those he finished changed art forever, from experimental portraits like La Belle Ferronnière to large-scale religious scenes that reshaped how viewers experienced sacred stories.

Key Leonardo da Vinci artworks include:

- The Last Supper (1490s CE, Milan) — A wall painting for the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie, showing the moment Christ announces that one of the apostles will betray him. Leonardo arranged the figures in a dramatic pattern of gestures and expressions, using perspective to lead the viewer’s eye to Christ at the center. The work became a model for narrative painting across Europe.

- Mona Lisa (c. 1503–1506 CE, Florence/France) — Perhaps the most famous painting in the world, also known as La Gioconda, this portrait combines subtle lighting, a mysterious smile, and a dreamlike landscape. Leonardo’s use of sfumato (smoky shading) makes the transitions between light and shadow soft and lifelike, giving the face an unusual psychological depth.

Major Works at a Glance

| Work | Medium | Date (approx.) | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Last Supper | Mural painting | 1495–1498 CE | Redefined narrative drama, gesture, and perspective in religious art. |

| Mona Lisa | Oil portrait | c. 1503–1519 CE | A benchmark for lifelike shading (sfumato) and psychological presence. |

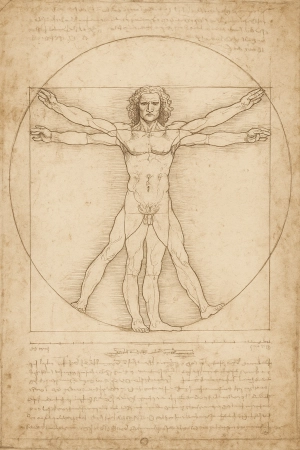

| Vitruvian Man | Pen-and-ink drawing | c. 1490 CE | An iconic fusion of classical learning, geometry, and anatomical study. |

Leonardo’s portrait work ranges from the enigmatic La Belle Ferronnière to the refined Lady with an Ermine, often linked to Cecilia Gallerani at the Milanese court. Another key early portrait is Ginevra de’ Benci — today in Washington, D.C., and widely noted as the only painting by Leonardo permanently displayed in the Americas.

Early religious paintings such as the Annunciation and other small devotional works show him experimenting with perspective, light, and landscape backgrounds that already hint at the atmospheric style of his later masterpieces.

These works are not just masterpieces of technique. They show Leonardo da Vinci’s contribution to art and science: he used geometry, optics, and anatomical study to make painting a tool for understanding the world.

What makes Leonardo unusual is that the same habits power both sides of his legacy. He painted slowly and revised relentlessly — but he drew constantly. The notebooks show how his art fed his science, and how his science, in turn, sharpened his art.

Leonardo da Vinci Drawings and Notebooks

While his paintings are iconic, many of the most important Leonardo da Vinci facts are hidden in his notebooks. Written in tight mirror-script and filled with sketches, they reveal a mind that never stopped investigating.

His drawings and notebooks include:

- Anatomical studies of muscles, bones, and organs, based on dissections of human bodies

- Detailed sketches of plants, water flows, and geological formations

- Designs for machines, from cranes and pumps to weapons and stage devices

- Notes on optics, perspective, and the behavior of light and shade

Among his most famous sheets is the Vitruvian Man, a study of ideal human proportions inscribed in a circle and square after the ancient author Vitruvius, often used as a symbol of the union of art, anatomy, and geometry. Much of his surviving written work is preserved in great compilations such as the Codex Atlanticus in Milan, the Codex Arundel in London, and the Codex Leicester, a notebook of scientific reflections on water, fossils, and astronomy now held in a private collection.

For Leonardo, drawing was a form of reasoning. He believed that to understand nature, one must see it accurately. These pages are key evidence for why Leonardo da Vinci is called a polymath: he moved with ease between artistic, scientific, and engineering problems, using the same disciplined observation for all.

Leonardo da Vinci Inventions and Engineering Visions

Machines of War and Peace

Leonardo spent much of his career working as an engineer and designer for powerful patrons, especially the Sforza dukes in Milan.

In Milan, he presented himself as a military engineer, proposing solutions for defense, logistics, and siege craft in an era increasingly shaped by artillery. (For the wider battlefield shift, see Knights to Cannons: The Gunpowder Revolution). His notebooks show ideas for:

- Fortifications and defensive walls

- A giant crossbow and multi-barrel guns

- Armored vehicles resembling early tanks

Many of these Leonardo da Vinci inventions were never built. Some were too speculative for the technology of his day. Yet they demonstrate his ability to combine classical knowledge with new mechanical ideas.

He also designed peaceful technologies:

- Canal and river projects to improve transport and prevent flooding

- Machines for lifting and moving heavy stones

- Devices for textile manufacturing and other crafts

In this, Leonardo stood alongside other innovators of the Renaissance age of change, from the printers discussed in The Printing Press and the Birth of the Modern World to political and military leaders like Mehmed II, explored in your 15th-century coverage.

Flight, Anatomy, and the Study of Life

Leonardo’s most famous dream was human flight. He analyzed bird wings, air currents, and muscle structure, filling pages with drawings and notebooks on:

- Ornithopters (wing-flapping machines)

- Parachute-like devices

- Early concepts of gliders and helicopters

Though these devices were never successful in his lifetime, they show Leonardo da Vinci as artist and scientist working together. His knowledge of anatomy and motion informed both his paintings and his engineering.

Similarly, his anatomical research aimed to create the most accurate possible understanding of the human body. He studied bones, muscles, the heart, and the nervous system, often in partnership with physicians. These investigations not only improved his art but also made him one of the most advanced anatomical observers of his era.

Leonardo is often credited with inventing devices like the tank, helicopter, parachute, or flying machine — but many of these claims flatten a more interesting reality. His notebooks preserve bold designs and mechanical reasoning, yet later scholarship frequently questions how direct the line is between his sketches and later working machines. In other words, his influence often lies in expanding imagination and method, not in single-handedly “inventing” modern technology.

How Leonardo da Vinci Changed the World

Leonardo da Vinci’s Contribution to Art and Science

How did Leonardo da Vinci change the world? His direct influence can be seen in several areas:

-

Artistic innovation

He raised the standard for realism, emotion, and composition in painting. His approach to light, perspective, and anatomy influenced generations of artists across Italy, France, and beyond. The Mona Lisa and The Last Supper became reference points for portraiture and religious art.

-

Scientific illustration and observation

Leonardo treated images as a scientific tool, demonstrating that clear drawings could communicate complex ideas. His approach anticipated later scientific atlases, anatomical textbooks, and technical diagrams.

-

Engineering imagination

Even when his inventions were not built, the concepts — like flying machines, armored vehicles, and complex hydraulic systems — expanded the range of what engineers dared to plan. His blending of theory and practice helped define the idea of the modern engineer.

-

The ideal of the polymath

Leonardo shaped the cultural idea of the multi-talented individual who unites art and science. This ideal still influences education and creativity today, from interdisciplinary research to STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Mathematics) programs.

In short, Leonardo da Vinci’s impact on history lies not only in what he personally built or painted, but in the model of curiosity and creativity he left behind.

Why Leonardo da Vinci Is Considered a Genius and Polymath

What Made Leonardo a Renaissance Genius?

Several qualities explain why Leonardo da Vinci is considered a genius:

- Relentless curiosity — He asked questions about everything: how water moves, how birds fly, how emotions appear on the human face.

- Precision of observation — His studies are not vague sketches; they are precise records, based on repeated viewing and measurement.

- Cross-disciplinary thinking — He used geometry to improve perspective in painting, anatomy to inform sculpture, and engineering principles to shape stage designs and military plans.

- Original problem-solving — Instead of merely copying older models, he tried to redesign machines, rethink urban layouts, and improve artistic techniques.

These traits show why Leonardo da Vinci is called a polymath. He was not simply talented in many fields; he actively connected them, making Leonardo da Vinci’s contributions to the Renaissance broader than any single profession.

Leonardo da Vinci in a Changing World

Leonardo’s life unfolded at a time of intense transformation. While he was painting and designing for the courts of Florence, Milan, and France:

-

The printing press was spreading texts and images more widely than ever before (see the article The Printing Press and the Birth of the Modern World ).

-

Rulers and conquerors such as Mehmed II were reshaping the political map between Europe and the Ottoman world.

-

Explorers like Christopher Columbus launched voyages that connected Europe to the Americas (see article Christopher Columbus: The 1492 Voyage to the Americas).

-

New ideas about religion, power, and knowledge were emerging, eventually leading to conflicts such as those examined in The Inquisition and the social upheaval that followed events like The Black Death.

Understanding Leonardo alongside figures like Joan of Arc, the builders of Machu Picchu, or Vlad the Impaler helps show that the Renaissance was not just an artistic moment. It was a global process of change in technology, belief, and empire.

Legend, Mystery, and Historical Debates

As with many famous figures, legend and speculation surround Leonardo da Vinci. Popular culture often imagines him as a secretive figure hiding codes and conspiracies in his paintings. While this makes for dramatic novels and films, historians focus on more grounded Leonardo da Vinci facts:

- Limited surviving works — Many paintings and sculptures have been lost, damaged, or left incomplete, leading to debates about attribution.

- Unfinished projects — His tendency to move on to new ideas before finishing older ones has given him a reputation as both brilliant and inconsistent.

- Personal life — Documentation about his private beliefs, relationships, and inner life is fragmentary, leaving room for speculation.

Historical debates also continue over issues like how accurate some of his anatomical studies were, or how directly later engineers drew from his notebooks. Yet these disputes only underline the richness of his legacy.

Last Years in France and Enduring Legacy

In his final years, Leonardo accepted an invitation from King Francis I of France. Around 1516 CE, he traveled to Amboise, where he lived in the manor of Clos Lucé. There he worked as a kind of court sage, advising on artistic and engineering projects and continuing to sort and revise his drawings and notebooks.

Leonardo died on 2 May 1519 CE. After his death, his notebooks were scattered among students and collectors, only gradually being studied and published in later centuries. As they became better known, the image of Leonardo da Vinci the genius grew. He came to symbolize the entire spirit of the Renaissance: confident, experimental, and endlessly curious.

Today, his influence appears in museum galleries filled with artworks inspired by his techniques; in engineering, architecture, and design fields that celebrate cross-disciplinary thinking; and in popular fascination with “Renaissance men and women,” people who refuse to be limited to a single field. For educators, students, and history enthusiasts, Leonardo offers both a case study in Renaissance creativity and a reminder that real understanding often comes from combining different ways of seeing the world.

FAQ: Key Questions About Leonardo da Vinci

How did Leonardo da Vinci change the world?

He transformed painting through works like the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, developed advanced methods of scientific illustration, imagined new types of machines, and modeled the ideal of a person who unites art and science. His influence on art, engineering, and the idea of the Renaissance genius continues today.

Why is Leonardo da Vinci considered a genius and polymath?

Leonardo mastered multiple fields—painting, sculpture, anatomy, engineering, architecture, and more—and connected them in creative ways. His notebooks show original thinking, careful experiments, and solutions to real-world problems, which is why he is widely regarded as a polymath.

What are the most important Leonardo da Vinci inventions?

Many of his inventions were designs rather than working machines, but stand-out ideas include flying devices, armored vehicles, improved canal systems, and innovative weapons. Even when they were not built, these Leonardo da Vinci inventions helped expand the horizons of Renaissance engineering.

Why was Leonardo da Vinci considered a “Renaissance man”?

He embodied the Renaissance belief that knowledge connects: painting relies on geometry and optics; anatomy improves realism; engineering depends on observation and drawing. Leonardo didn’t just collect skills — he linked them, using art as a tool to understand how the world works.

Did Leonardo da Vinci really invent the helicopter or tank?

He sketched memorable designs that resemble later machines, but that doesn’t mean he built working versions or directly “invented” modern technology. Many popular attributions are debated, and the safer conclusion is that Leonardo pioneered a way of thinking — combining mechanical imagination with careful drawing — more than a list of finished inventions. :contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}

Sources & References

- Martin Kemp, Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man (Oxford University Press, 2006).

- Walter Isaacson, Leonardo da Vinci (Simon & Schuster, 2017).

- Luke Syson (ed.), Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan (National Gallery, 2011).

- Charles Nicholl, Leonardo da Vinci: The Flights of the Mind (Penguin, 2005).

- Exhibition and educational materials from institutions such as the Louvre, the Uffizi Gallery, and the Royal Collection.

More Articles