Machu Picchu: The Lost City of the Incas - Untold Story

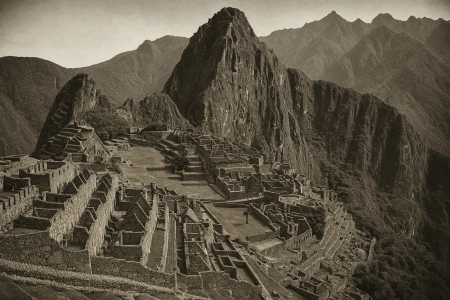

Machu Picchu clings to a knife-edge ridge high above the Urubamba River—where stone meets cloud and empire meets myth.

Reading time: ~8 min

Introduction

Riding a knife-edge ridge and wrapped in cloud forest, Machu Picchu is one of the world's most evocative archaeological sites. Perched at about 2,430 meters (7,970 ft) in Peru's Andes, the Inca citadel blends dramatic terrain with astonishing stonework—terraces, canals, and temples fitted so tightly that blades can't slip between the blocks. Long unknown to the outside world and sometimes called the “Lost City of the Incas,” Machu Picchu was revealed to international audiences in 1911 by Hiram Bingham. Yet local communities already knew of the ruins, and modern archaeology paints a richer story of who built it, when, and why. This article explores Machu Picchu's setting, design, purpose, discovery, and enduring legacy—with practical insights for curious readers, students, and travelers alike.

Where Is Machu Picchu—and Why Here?

Machu Picchu sits on a narrow saddle between Machu Picchu (“old peak”) and Huayna Picchu (“young peak”), above a bend of the Urubamba River. The site's altitude and setting are not mere backdrop—they are central to Inca planning. Terraces stabilize steep slopes, expand arable land, and manage water; channels and fountains deliver spring water with remarkable efficiency and durability.

Side fact: The altitude (≈2,430 m / 7,970 ft) places Machu Picchu in the cloud-forest belt, where orchids, hummingbirds, and mist are part of the experience—and the conservation challenge.

The Inca Citadel: Plan, Symbols, and Stone

Archaeologists often divide Machu Picchu into agricultural and urban sectors separated by a broad plaza. Around two hundred structures—dwellings, storage, and ritual spaces—are knitted into the terrain by terraces and stairways. The site's ashlar masonry (carefully shaped blocks set without mortar) shows the Inca mastery of local granite and seismic-resistant design.

Machu Picchu History: The Sacred Landscape

Temples anchor the urban core: the Temple of the Sun (Torreón), Temple of the Three Windows, Principal Temple, and the enigmatic Intihuatana (“hitching post of the sun”). The Intihuatana's carved pillar aligns with solar events, suggesting calendrical or ceremonial functions. What is clear is the Incas' careful choreography of architecture, sightlines, and celestial cycles.

Roads, Gates, and Views

Machu Picchu connects to the imperial road network. Approaching via the Inti Punku (Sun Gate) on the Inca Trail frames a ceremonial vista: terraces spilling down toward the Urubamba, the city cradled between twin peaks. The topography itself—rivers, ravines, and sacred mountains (apus)—forms a ritual landscape as much as a defensive one.

Who Built Machu Picchu—and When?

Most scholars interpret Machu Picchu as a royal estate of the Inca emperor Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (r. c. 1438-1471), created in the mid-15th century at the empire's apogee. Its elite residence compounds, ritual precincts, and agricultural zones fit the pattern of a royal retreat tied to power, ceremony, and display.

Recent radiocarbon work nudges the chronology earlier: human remains indicate occupation may have begun in the 1420s, refining our timeline. This does not overturn the Pachacuti association; rather, it sharpens our picture of when royal building began and how long the estate flourished.

Debate snapshot: Earlier theories cast Machu Picchu as a fortress, a nunnery, or even the true last Inca capital. Modern consensus favors a royal-estate model with sacred, agricultural, and astronomical roles interwoven.

“Lost” and Found: From Local Knowledge to Global Fame

On July 24, 1911, Yale lecturer Hiram Bingham reached the ridge with the help of local residents and brought Machu Picchu to international attention. His expeditions, photographs, and the April 1913 special issue of National Geographic transformed the site into a global icon. Importantly, Bingham did not “discover” Machu Picchu in an absolute sense; people living in the area already knew of the ruins and cultivated terraces nearby.

Bingham initially believed he had found the Inca “Lost City” of Vilcabamba, the last royal stronghold against the Spaniards. Subsequent research identified the true last refuge at Espíritu Pampa, confirming that Machu Picchu was something else entirely—an interpretation that underscores how archaeology evolves as new evidence accumulates.

A related chapter concerns the artifacts taken to Yale for study. After a long dispute, Peru and Yale reached an agreement in 2010 to return the collection, now exhibited in Cusco in partnership with UNSAAC.

Engineering Genius in a Fragile Place

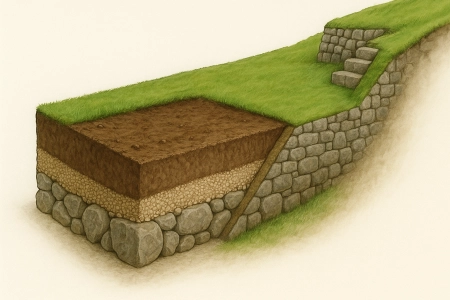

Machu Picchu endures not because it escaped time, but because Inca engineers anticipated it. Builders used trapezoidal doorways, inward-slanting walls, and interlocking blocks to dissipate seismic forces. Terraces acted as retaining walls and living drainage systems—stone, gravel, and soil layers that wick water downward and outward.

Equally impressive, a spring-fed canal and series of fountains met daily needs while shedding excess flow during cloudbursts. These choices reveal an intimate dialogue with one of the planet's most challenging settings and help explain the citadel's longevity.

UNESCO Status, Stewardship, and Sustainable Visits

Designated a World Heritage Site in 1983, Machu Picchu is recognized for both cultural and natural values—rare among listings. The inscription covers the citadel and the surrounding sanctuary with remarkable biodiversity. With renown come risks: visitor pressure, landslides, and ecosystem stress. Timed entries, route planning, and reinvestment of tourism revenue aim to balance access with preservation.

- Prepare for altitude & weather: Cloud forest conditions can shift quickly; carry layers and water.

- Follow circuits & timings: They protect fragile masonry and vegetation while keeping traffic flowing.

- Think beyond the postcard: Sacred Valley and Vilcabamba sites spread benefits and pressure more evenly.

Conclusion: A City Between Earth and Sky

Machu Picchu compresses an empire's ambition into stone—an Inca citadel that fuses engineering with sacred landscape. Royal estate, ceremonial center, and observatory: these roles overlap in a place where terraces become architecture and mountains become monuments. From Pachacuti's court to Bingham's photographs and today's carefully managed visitation, the “untold story” is less a single revelation than a century of evolving insight—an invitation to keep learning while treading lightly on a ridge between the Andes and the Amazon.

Sources & References

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu (inscription dossier and site notes).

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, entries on Machu Picchu and Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui.

- Yale News (2021) and Smithsonian Magazine (2021) on AMS radiocarbon dating refining occupation chronology.

- National Geographic (1913 special issue; later features) on Hiram Bingham's expeditions and photography.

- PBS NOVA interviews and Ken Wright, civil-engineering analyses of terraces, canals, and fountains.

- Studies identifying Espíritu Pampa as the final Inca refuge in Vilcabamba.